Human-environment interrelationship

-

Invitation to Book Launch: What is the Magic of Pang Sua Woodland? (18 May 2024)

I learnt from the Nature Society (Singapore) that they are launching the second edition of their book on Pang Sua Woodland next Saturday evening, which is the second installation of their Green Rail Corridor book series. Having read the first edition of Pang Sua Woodland, I eagerly look forward to reading their second edition. If… Continue reading

-

Habitat enhancement session, Lim Chu Kang nature park, 30 April 2024

It was a pleasure volunteering with NParks and other members of the public on Tuesday afternoon. We learnt from the staff guides how to do weeding, mulching and watering to care for the tree saplings that have been planted recently. While loosening the soil, I saw little creatures emerging from beneath, such as a toad,… Continue reading

-

Pulau Ubin cleanup (28 April 2024)

The hot sweltering weather failed to dampen the energy and enthusiasm of over 30 volunteers who visited Sungei Durian for a beach cleanup last Sunday. The event was organised by Joseph Zexeong Tan and attended by volunteers including members of the Singapore Titans Eagles Club (Singapore Region) and also Korbstein family. Together, they cleared away… Continue reading

-

Permaculture gardens: visiting and volunteering

It was a pleasure to be shown around an urban permaculture garden at Mindful Space, Winstedt Road, which I visited between my lunch and dinner shifts on 25 February 2024. Our host Catherine Loke, President of The Circle for Human Sustainability, graciously took time to show me and a few other guests around the garden.… Continue reading

-

Book highlights: “Dynamic Environments of Singapore”

I borrowed a book called “Dynamic Environments of Singapore” by Daniel Friess and Grahame Oliver (published in 2015) from a public library recently, which I find quite informative, though slightly dense. Here’s sharing some noteworthy details: Which of these points stands out for you the most? For me, the first two points particularly stand out… Continue reading

-

Beach cleanup at Sungei Durian, Pulau Ubin (24 February 2024)

Last month, the Pulau Ubin cleanup session was postponed due to inclement weather during the northeast monsoon season. Thankfully, the weather was dry when we embarked on our first beach cleanup session of the year 2024 yesterday, albeit a tad too hot and humid in the mid afternoon, causing us to perspire even before we… Continue reading

-

The animals’ lawsuit against humanity (A modern play adapted from an ancient tale)

On Friday evening (26 January 2024), I attended a meaningful community reading of the classic interfaith and multicultural fable, led by environmental and natural health educator Betty L Khoo-Kingsley. This very interesting ancient animal rights tale was written in the 10th Century by a Muslim philosophy group from Iraq. The participants created their own masks… Continue reading

-

Sungei Buloh wetland reserve: 30th Anniversary | World Wetlands Day celebration with Biking 4 Biodiversity

On 25 November 2023, I attended the celebration of the 30th anniversary of Sungei Buloh wetland reserve at the main visitor centre. Sungei Buloh has gone from strength to strength, and has been transformed from glory to glory since its inception in 1993, thanks to conservation efforts by Nature Society (Singapore) and volunteers among the… Continue reading

-

Rescue of an injured waterhen at West Coast Vale

On 9 January 2024, I was involved in the rescue of an injured bird, which I passed by around 7.30 pm while cycling along West Coast Vale during my dinner shift. After stopping to examine the stationary body of the bird in the middle of the road, I recognised it was a white-breasted waterhen and… Continue reading

-

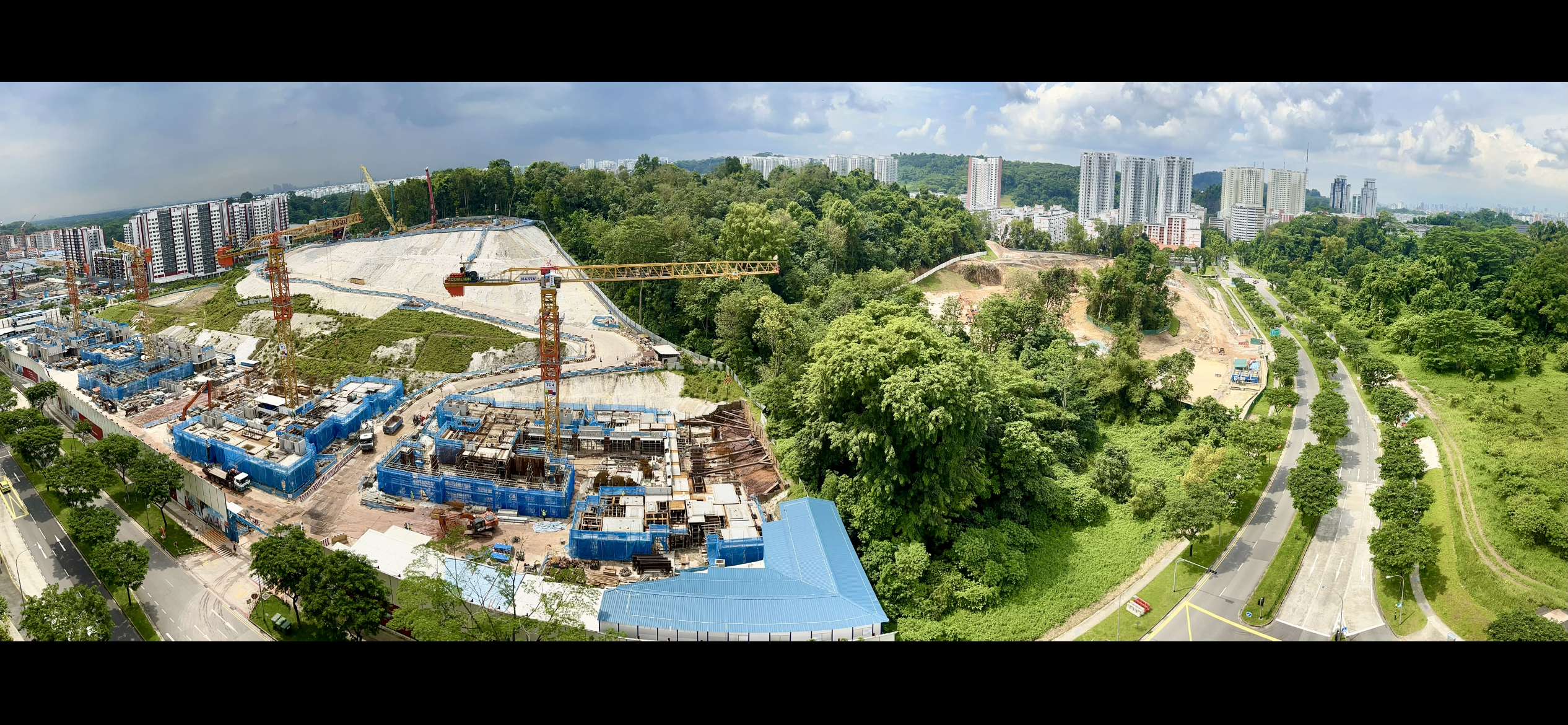

Impact of deforestation and urbanisation on parakeets and mynahs in Singapore

Much like humans and other primates, certain bird species such as parakeets and mynahs are social creatures. Towards end of the day, parakeets and mynahs would flock to their roosting trees to congregate, chat/chatter loudly to exchange notes and greetings before retiring to bed. One difference is that parakeets are forest-dependent birds and prefer to… Continue reading