May 2022

-

International Day of Biological Diversity 2022: A celebration of birds seen in Singapore

22 May is the International Day for Biological Diversity. I was inspired to do a video as a preview to some of the common and less common wildlife seen in Singapore in the past couple of years. Some of the videos were shot during my solo recces, while others were taken during group hikes (thanks… Continue reading

-

What can we learn from our younger generations about climate change?

“Climate change ain’t political; it’s parental.” – Prince Ea Indeed, climate change is a result of many parents, especially those in positions of influence and privilege, particularly in corporations and governments, who choose to live an unsustainable lifestyle or make decisions and policies that conform to the capitalistic economic system at the expense of our… Continue reading

-

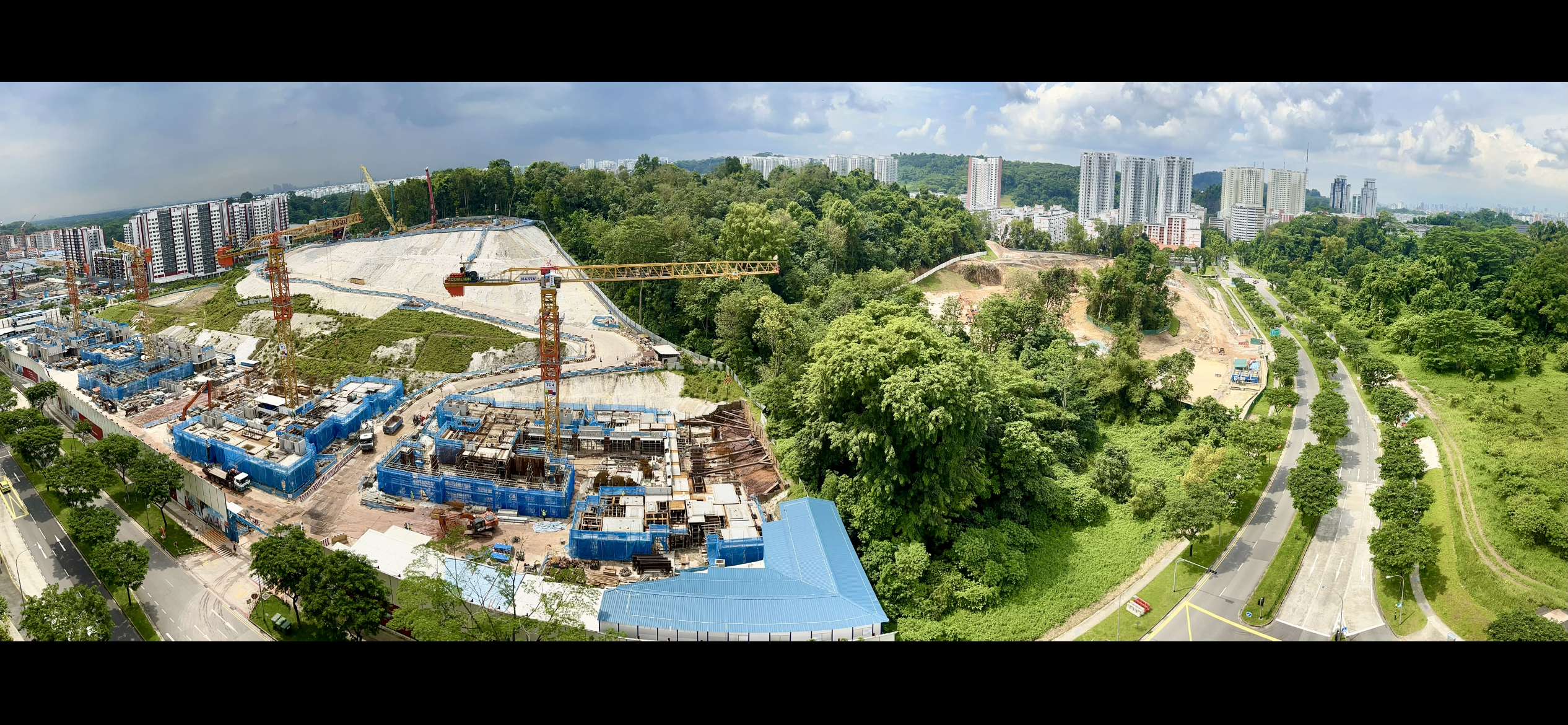

My feedback to HDB on Environmental Impact Studies (EIS) report regarding Keppel Club Site

Background In 1819, Singapore was almost fully covered by primary rainforests: 82% are lowland evergreen rainforests, 13% mangroves and 5% freshwater swamp forests (according to NParks). These natural vegetation types are best suited to the hot, humid and wet tropical climate in Singapore, which ensure optimal functioning of a healthy natural ecosystem. After two centuries… Continue reading

-

My feedback to HDB on Environmental Baseline Study report regarding Choa Chu Kang N1 (including Pang Sua woodland and river canal)

Here is my feedback on Housing and Development Board (HDB)’s Environmental Baseline Study (EBS) report for Choa Chu Kang N1, which includes Pang Sua woodland and river canal, in Singapore. I understand that this forest patch is one of the few sizeable natural habitats (which include Kranji woodland, Clementi forest and Alexandra woods) located along… Continue reading