The much publicised “Tengah Forest Town” development that is planned to clear 90% or more of the original forest has become a controversy. For a start, Tengah forest (aka Bulim forest) has a very impressive record of 262 fauna species, of which 60 are regarded as forest-dependent wildlife species and at least 44 species are nationally threatened, according to HDB’s baseline report dated 2017. The forest also has at least 33 species of plant life with “conservation significance”, as well as 159 significant large trees, of which 90% belong to the fig family (Moraceae). (Photos by Jimmy Tan)

This diagrammatic map illustrates that Tengah forest is a vital conduit and habitat supporting biodiversity and ecological connectivity between Western catchment area and Central catchment area, which are Singapore’s main terrestrial “green lungs”. They provide essential ecosystem services, including removing pollutants, purifying the air, absorbing carbon emissions, cleaning the soil, preventing flash floods, cooling the urban heat island effect, and providing food and shelter for living organisms. Thus, they potentially save billions of dollars’ worth of social, health and environmental costs that would be incurred if the forests were removed or reduced. (Satellite image dated May 2021 by Akihiko Hoshide)

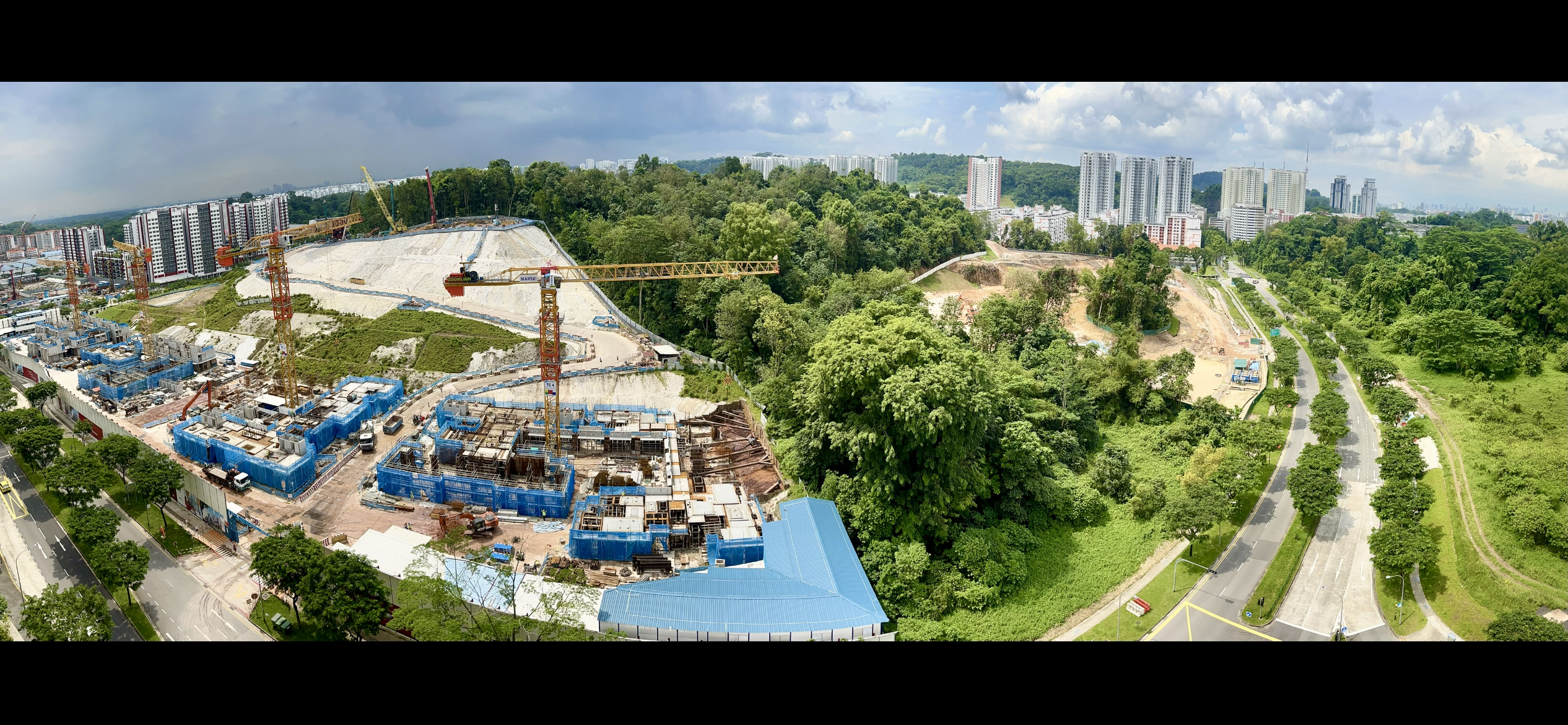

It has been about two years since Housing and Development Board (HDB) has started development works in the 700-ha Tengah forest in early 2019 after fencing up its perimeter. It has resulted in the clearance of about 30% or more (or 210 ha or more) of the forest so far, in a bid to build a “forest town” in Singapore, which would be about the same size of Bishan housing estate.

To date, HDB has launched thousands of new BTO (Build-To-Order) apartment flats in parts of Tengah area in November 2018, May 2019, November 2019, August 2020, November 2020 and February 2021. In May 2021, another 782 HDB BTO flat residential units were launched in Tengah.

However, although an environmental baseline study (EBS) was done in Tengah forest in 2017, we urgently need to reconsider the ramifications of Tengah forest town development because concerns about rapid deforestation and urbanisation in Singapore have been raised by Nature groups and members of the public, especially in recent years.

Since the early 2010s, more and more people in Singapore have been voicing their concerns about the loss of wild green spaces and biodiversity resulting from the destruction of regenerating secondary rainforests, such as Lentor-Tagore forest, Bidadari forest, Tengah forest, Pasir Ris forest, Kranji woodlands, Jurong Eco Garden nature trails, and Bukit Batok Hillside Park area forest. These forests have been sacrificed to varying degrees for development, despite comprehensive descriptions of wildlife sightings having been recorded (and alternative sites for development having been proposed in the cases of Tengah forest and Bukit Batok Hillside Park area).

More recently, three petitions for conserving Bukit Batok Hillside Park area, Clementi forest and Dover-Ulu Pandan forest have been started in Singapore since last year, garnering over 13,000 signatures, 19,000 signatures and 50,000 signatures respectively as of May 2021.

These petitions have highlighted various negative consequences of continual deforestation, such as increased urban heat island effect contributing to climate change, endangerment of forest-dependent species and biodiversity loss, and threat to our physical and mental well-being as well as our very existence.

As the fate of Tengah forest is still hanging in the balance, this blog post serves to provide examples of its rich biodiversity and its indispensable function as an important ecological corridor connecting Western catchment area and Central catchment area. It also aims to highlight the fact that Tengah forest in its current state is crucial for dealing with climate emergency and biodiversity loss as well as improving our quality of life.

In view of the importance of Tengah forest (which we will read about below), we urgently need to preserve the rest of its remaining area as much as possible, or at least 30 to 50 percent of its original 700-ha size (or 210 to 350 ha). In order to do so, we need to:

- heed Covid-19 pandemic (and resurgence of community cases) and other warning signs seriously and halt or minimise deforestation in Singapore, including in Tengah forest

- treat climate emergency as it really is because we are running against time to deal with its existential threat to our survival, and Tengah forest is big enough to have a significant impact on our microclimate

- protect our biodiversity in Tengah forest (and its connecting corridors and core nature areas) from further loss and endangerment of species

- establish sizeable wildlife corridors and core habitats areas in Tengah forest in order to maintain a healthy ecosystem that benefits humans, flora and fauna

- focus on redeveloping alternative sites or brownfield sites such as underutilised lands and abandoned schools etc in order to achieve a better and more sustainable future for ourselves and our future generations.

1. We need to heed Covid-19 pandemic (and resurgence of community cases) and other warning signs seriously and halt or minimise deforestation in Singapore, including in Tengah forest.

The urgency to protect our forests is compounded not only by worsening climate change but also increasing loss of forest habitats in Singapore. It has resulted in loss of biodiversity, increasing incidences (and recurrences) of flash floods, zoonotic virus pandemic (including COVID-19 virus variants), dengue fever and malaria cases, as well as animal roadkills (resulting in deaths of endangered Sambar deer, Sunda pangolins, palm civets, etc) and human-wildlife conflicts (including the unprovoked wild boar attacks on humans in urban areas that have encroached on their forest habitats).

In particular, researchers around the world have been giving warnings about the destruction of tropical rainforests sparking pandemic diseases. Prominent naturalist Jane Goodall has blamed the emergence of Covid-19 on the over-exploitation of the natural world, which has seen forests cut down, species made extinct and natural habitats destroyed.

In view of the possibility that the coronavirus has made the jump from animals to humans in China since late 2019, the Covid-19 resurgence in local community cases in Singapore in late May this year is a cause of concern, especially in the wake of continual deforestation and urbanisation.

On 4 June 2021, scientists behind a new independent taskforce, which is hosted by Harvard University and will report to the coalition on Preventing Pandemics at the Source, said that ending the destruction of nature to stop outbreaks at their source is more effective and cheaper than responding to them.

“Recent research estimated the annual cost of preventing further pandemics over the next decade to be $26bn (£18bn), just 2% of the financial damage caused by Covid-19. The measures would include protecting forests, shutting down risky trade in wildlife, better protecting farm animals from infection and rapid disease detection in wildlife markets.”

“World leaders ‘ignoring’ role of destruction of nature in causing pandemics” (4 June 2021)

Incidentally, earlier this year, we have been talking about adopting science-based approach and nature-based solutions in dealing with wildlife management and environmental issues. In the case of Tengah forest, National Development Minister Desmond Lee said:

“we recognised that the forests at the future Bukit Batok Hillside Nature Park and Bukit Batok Central Nature Park are important stepping stones between the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, and the future Tengah Forest Corridor. That is why we dedicated these nature parks as part of the Bukit Batok Nature Corridor – they will be kept lushly forested, so that they can strengthen not just the area’s green network, but also ecological connectivity between the Nature Reserve and Tengah.”

Speech by Minister Desmond Lee: A City in Nature, a Greener Urban Environment (4 March 2021)

While it is good that we are taking the science-based approach towards wildlife management and forest conservation, we will be ignoring the scientists’ warnings about pandemics and environmental destruction at our peril. In other words, the conservation of Tengah forest (and other secondary forests) is a non-negotiable measure that we must take in order to deal with the urgent public health and environmental crises facing us.

2. We need to treat climate emergency as it really is because we are running against time to deal with its existential threat to our survival, and Tengah forest is big enough to have a significant impact on our microclimate.

On 1 February 2021, in response to the petitions and the questions raised by various Members of Parliaments (MPs) on behalf of concerned residents and citizens, the Singapore Parliament has rightly declared the issue of climate change a global emergency, recognising it as a “threat to mankind” that requires a concerted effort to “deepen and accelerate efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change, and to embrace sustainability in the development of Singapore”.

However, when the SG Green Plan 2030 was launched on 10 February 2021, it did not mention about slowing down or stopping deforestation. This is worrying because land use change or deforestation is a significant cause of carbon emissions and contributor to climate change, resulting in debilitating consequences, such as more extreme weather changes, more frequent flash floods, and so on.

While the Green Plan includes the one-million tree planting programme, which is laudable, botanist Shawn Lum cautioned that “tree planting is beautifully complementary to, and not a substitute for, the care and protection of existing forest habitats.”

In fact, one of the most effective (and cost-effective) nature-based solutions to combat climate change, as also proposed by conservation scientist Professor Koh Lian Pin, is to “protect Singapore’s remaining forests and avoid further emissions from deforestation“.

Moreover, replanting trees, or reforestation, takes decades for the trees to grow and mature under the right conditions, and cannot replace our need for forest conservation, since planting trees does virtually nothing to protect the local biodiversity and ecosystems fully. Also, if we plant trees of similar species for aesthetic landscaping to create manicured parks and gardens, it is like developing monocultures that are incapable of recreating plant diversity as per their existence in the wild.

Although the SG Green Plan may envision Singapore becoming a metropolis like London or New York, we need to bear in mind that unlike these cities in cool temperate countries, Singapore is a small tropical island-state. Since we experience hot, wet and humid tropical climate at the Equator, we cannot keep removing our default natural vegetation, which includes tropical rainforests, freshwater swamp forests and mangrove forests, without facing dire consequences on our health, safety and well-being as well as our flora and fauna.

According to the Meteorological Service Singapore’s Centre for Climate Research Singapore, last year’s annual mean temperature of 28 degrees Celsius was half a degree higher than the long-term average, making 2020 the eighth warmest year on record. Singapore’s official meteorological agency also noted a recent sharp rise in temperatures and warned that maximum daily temperatures could reach 40 degrees Celsius by as early as 2045.

Singaporean climate change scientist and professor Winston Chow attributed the rising temperatures to a phenomenon known as the “Urban Heat Island Effect,” which occurs when cities replace natural land cover with dense concentrations of concrete, pavement, buildings, and other surfaces that absorb and retain massive amounts of heat. He added:

“Singapore has definitely been getting hotter and every degree counts. The hot weather we’ve been experiencing recently is not only a clear indicator of climate change but also the effect of how rapidly urbanization alters local climates.”

“Can Singapore Control Its ‘Diabolical’ Hot Weather?” (5 March 2021)

Now that Singapore is heating up twice as fast as the planet due to rapid deforestation and urbanisation, if we continue to remove our few remaining secondary rainforests, such as Tengah Forest, we may soon reach a tipping point at which heat stress affects both human health (through greater risks of dehydration, heat strokes, etc) and carbon dioxide uptake by trees (due to damage to leaf tissue and declining tree health).

For example, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency:

“Climate change increases the risk of illness through increasing temperature, more frequent heavy rains and runoff, and the effects of storms. Health impacts may include gastrointestinal illness like diarrhea, effects on the body’s nervous and respiratory systems, or liver and kidney damage.”

In terms of economic and financial implications, it is likely that we will be spending billions of dollars improving healthcare infrastructure and access as well as covering increased medical bills when we see a rise in cases of heat waves affecting the human body and more severe storms and more frequent floods resulting in water-borne illnesses. There are also intangible costs, such as loss of reputation, lost recreation and the psychological impact on people, all of which feed back to the economy, as noted by Nanyang Technological University (NTU)’s head of economics, Euston Quah.

Similar concerns about climate change on the environment have also been raised by scientists around the world. For example, according to Professor Daniel Murdiyarso, principal scientist at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), based in Bogor, Indonesia:

“Deforestation or removal of rainforests has certainly reduced the landscape capacity to absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide. Combined with the effect of climate change, it has caused the ecosystem to be more vulnerable to extensive droughts and wildfires. Rainforests are very fragile. Large-scale disturbance like deforestation or fires will not give them the chance to renew themselves.”

“Forests are needed to absorb carbon, but the overheating planet might soon flip a critical switch” (CNA, updated 4 May 2021)

Already, scientists are concerned that as much as 40% of the Amazon rainforest, which is more than 3,000 times the size of Singapore, may reach a tipping point in 50 years’ time, whereby it may collapse and morph into arid savannahs as a result of climate change.

So we cannot guarantee that we will not be spared from such an ecological catastrophe too, especially since our protected nature reserves occupy less than 5% of our total land area, while we continue to lose our spontaneous vegetation, which includes secondary forests, shrublands and scrublands, and which occupies only about 20% of our total land area.

(In contrast, Mauritius, also a tropical island like Singapore with a high human development index, has 47% of its total area occupied by forests. So, it may very well be a myth that we must keep on sacrificing our forests for economic development in order to enjoy a high standard of living and good quality of life.)

Thus, it is imperative for us to treat climate change as a real emergency and re-emphasise the importance of Tengah forest (as well as other secondary forests) for dealing with climate emergency and biodiversity loss as well as improving our quality of life.

3. We need to protect our biodiversity in Tengah forest (and its connecting corridors and core nature areas) in order to prevent further loss and endangerment of species.

Firstly, an environmental baseline study (EBS) had been initially done for Tengah forest by HDB. Given the findings of this baseline study, the vice-president of the Nature Society (Singapore) (NSS), Dr Ho Hua Chew has pointed out that Tengah forest harbours a rich biodiversity.

An academic paper on updating the classification system for secondary forests in Singapore has noted that rare, threatened or endangered species may be found in regenerating forests. Hence, nature groups and members of the public should be consulted as early as possible on urban planning before any environmental impact assessment (EIA) is carried out and before any developer is awarded a construction project contract tender for any forest patch.

Like Dr Andie Ang from the Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund also noted, even if delays were to occur, it is better off to consult green groups and residents at the review stages of the URA Master plan. This is so that we can “ensure a higher quality of urban planning, which can minimise the impact on the environment and improve the overall quality of life for residents. Feedback at an early stage would also help planners to understand what residents want and to build accordingly”.

As it were, the general public were apparently not consulted in advance to gauge if there was a significant demand for housing in Tengah forest before HDB conducted EIA in the forest several years ago. Notably in February 2021, one day after the latest batch of BTO flats were launched in Toa Payoh/Bidadari, Whampoa/Kallang, Tengah and Bukit Batok, the latter two appeared to be not quite popular for home buyers. As the Straits Times noted:

“Those who wish to live in the non-mature estates of Bukit Batok and Tengah may have better luck as application rates were relatively low yesterday evening.”

Thus, in view of the rich biodiversity in Tengah forest and the relatively low initial demand for housing in Tengah, we need to seriously reconsider the need to develop the rest of Tengah forest as originally planned. We should also focus on redeveloping brownfield sites within reasonable distance from existing town amenities and infrastructure, such as vacant lands, underutilised lands, abandoned schools, etc, as well as building taller apartment blocks where possible in order to make up for any shortfall of planned flat units.

Secondly, according to a Straits Times article dated 23 February 2021, National Development Minister Desmond Lee said that “a more comprehensive picture of Singapore’s nature areas and how they connect to one another will be developed. The idea is to map out the islandwide ecosystem and connectivity to better consider how specific sites connect to nature areas, buffers and corridors.”

Indeed, we do need to take into account the big picture of biodiversity on a national scale instead of treating the development of Tengah Forest Town merely as a localised or discrete project. Hence, we need to acknowledge that in view of the rich biodiversity in the regenerating secondary forests between the Western catchment area and Central catchment area (which include Tengah forest, Bukit Batok Hillside Park ridges, Bukit Gombak forest (aka Little Guilin or Bukit Batok Town Park), Bukit Batok Nature Park and Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, etc), it is paramount to preserve the remaining parts of Tengah forest as much as possible (which in fact is one of the largest contiguous patches of green space in Singapore, bigger than even the 163-ha Bukit Timah Nature Reserve).

This will ensure that the native wildlife, such as Sunda pangolins, Sunda colugos (or flying lemurs), palm civets, Malayan box turtles, green crested lizards and greater bamboo bats, have sufficient space to live, move, feed, reproduce and carry out pollination and seed dispersal, without ending up as animal roadkills or getting into conflicts with humans in residential areas, which may lead to injuries or even deaths.

As a testament to the rich biodiversity in Tengah forest, at least a dozen baya weavers’ nests have been found in the northeastern part of Tengah forest. This sighting, together with other wildlife sightings mentioned in this blog, suggests that there is abundant natural food supply and complex food webs of interconnected flora and fauna that already exist in the ecosystem.

From my understanding, HDB is currently doing a new Environmental Impact Study (EIS) in the north of Tengah, including the baya weavers’ nesting area that I have highlighted to them via OneService app. I was told that their EIS consultant will take into consideration my feedback when assessing the potential impacts from the development plans with mitigating measures to be recommended and implemented by the future contractor.

(It must be noted that the new EIS is being done in a smaller area within the original Tengah forest, which is already cleared in some parts. Hence, the results of the EIS may reflect lower biodiversity than before any construction work began in 2019, due to disturbances being caused to the flora and fauna by edge effects, light pollution, noise pollution, etc as a result of the forest clearances. In other words, this new EIS is unlikely to capture the full conservation value of the original Tengah forest, hence our review of the EIS report must take this reality into consideration.)

As for the beautiful flat yellow butterfly, it is described as rare in the forested plains of Singapore and Malaya, with only a few sightings in parts of Singapore, including Tengah forest. Moreover, according to Delvinder Kaur, junior animal care officer, Zoology, Wildlife Reserves Singapore, “insects are responsible for approximately 80% of the pollination out there. Pollination is needed for our crops, and that gives us food security”. Given Tengah forest’s close proximity to Kranji countryside where farms are plentiful in Lim Chu Kang and Neo Tiew areas, the proliferation of insects, such as bees and butterflies, in Tengah forest is crucial for pollination of crops in the nearby farms to ensure food security for us. This also means that we shouldn’t just focus on protecting rare, endangered and/or endemic species (as crucial as they are), but we should also seek to accommodate common species because they also contribute uniquely to functional diversity, and both rare and common species are all interrelated and interdependent in the ecosystem.

Both Sunda pangolins and straw-headed bulbuls are globally critically endangered, and their populations are also threatened by poachers for illegal wildlife pet trade. NSS has reported that the confirmed presence of the Sunda pangolin with a young in Tengah forest “reveals that Tengah forest is not just a foraging ground for the species but most notably a breeding ground as well”.

As for the straw-headed bulbuls, they have become extinct in Thailand and parts of Indonesia and are facing a decline in Malaysia. It is estimated that at least 202 individual straw-headed bulbuls are distributed over multiple forest patches, including Tengah forest, in Singapore, which has become a crucial global stronghold for preventing them from becoming extinct in the wild. It would be tragic if such critically endangered species were to disappear altogether in the wild right under our nose due to our neglect to take care of ecological connectivity (just like how the large forest gecko and cream-coloured giant squirrel became extinct after Bukit Timah expressway (BKE) was built in the 1980s) when we have the knowledge and the means to protect them and their natural habitats.

Notably, the presence of eagles (also known as raptors or birds of prey), which are apex predators at the top of a food chain, indicates a healthy, thriving ecosystem in Tengah forest, where there exists a complex food web consisting of plant producers, microorganisms, herbivores, carnivores and omnivores. Also, the endangered changeable hawk-eagles, near-threatened grey-headed fish eagles and near-threatened long-tailed parakeets are forest-dependent native wildlife, hence their populations may be adversely affected if we continue to destroy our secondary rainforests, such as Tengah forest, and replace their natural feeding and breeding grounds with parks, gardens and roadside trees around concrete buildings.

Like Mr Lim Liang Jim, Group Director of National Biodiversity Centre who oversees NParks’ Nature Conservation Masterplan, said:

“We really don’t know at this point in time how species interrelate. So, it could even be a butterfly effect. If you lose one small species, you will never know what it will result in the long term to the health of the forestry.”

(“It’s In Our Nature: Saving Our Wildlife“, Channel News Asia Documentary Episode 2)

(Note: The aforementioned insects, birds and mammals are just some examples of the numerous important native wildlife in Tengah forest. Do refer to Nature Society Singapore (NSS)’s Position Paper on HDB’s Tengah Forest Plan here for more details on its flora and fauna.)

4. We need sizeable wildlife corridors and core habitat areas in Tengah forest in order to maintain a healthy ecosystem that benefits humans, flora and fauna.

Firstly, while it is somewhat encouraging that the town planners have set aside 50 ha out of 700 ha to create a wildlife corridor of 100 m wide in the Tengah forest town development plan to facilitate animals’ movements as a connector, NSS feels that its effectiveness in helping the wildlife adapt to the change with this corridor is questionable.

According to NSS, the 100 m width will not be enough to mitigate disturbances for wildlife because 50 m is the standard buffer for a forest habitat on all flanks and there will not be any interior space. This will be tragic for the rich wildlife currently inhabiting the area.

Secondly, it is worrying that under the HDB’s plan, only up to 10% of Tengah’s original forest is retained. This means that half of the species there could be wiped out, based on an ecological rule of thumb, the NSS said. Even though HDB said that some 20% of the land in Tengah will be set aside for “green spaces”, the replanted young trees and crops in man-made parks and community gardens and farms cannot substitute the regenerating secondary forest in terms of ecosystem services and biodiversity support.

Thirdly, if we were to consider the percentage of forest cover found in housing estates in Singapore, Bukit Batok actually tops the list. It is estimated that Bukit Batok has 17% forest cover, because about 190 ha out of a total area of 1,113 ha is occupied by the forests in Bukit Batok Town Park (77 ha), Bukit Batok Nature Park (36 ha), Bukit Batok Hillside Park area Hill 1 and Hill 2 (30 ha), Bukit Batok East Forest (30 ha) and Bukit Batok Central Nature Park (17 ha).

Thus, it would be incongruous to proclaim Tengah as Singapore’s first “forest town” when its planned forest cover of a paltry 50 ha pales in comparison to that of its neighbouring town Bukit Batok. At this point, credit must be given to the town planners for having set aside 190 ha of the total area of Bukit Batok for the forests. Bukit Batok is a role model for other towns to emulate for its wild green spaces that provide essential ecosystem services and support biodiversity. It is also hoped that no further deforestation should be carried out in Bukit Batok after the unfortunate clearing of part of Bukit Batok Hillside Park area in February 2021 for housing development because the forests there are vital for ecological connectivity.

At the same time, we need to ask ourselves: “Will the word “forest” in the name “Tengah forest town” be merely used as a form of tokenism? Or will it be prioritised to honour the native species whose previous generations have existed and used the forest as a habitat and ecological corridor long before our forefathers arrived on this island?” If it is the latter, then we need to ensure that Tengah “forest town” lives up to its billing by preserving at least 30% to 50% of the original forest cover. May we refer to the map showing the two core areas for wildlife as proposed by NSS below?

As proposed by NSS’s position paper on Tengah Forest, “the eco-links/bridges that should be created as the essential part of the Tengah Nature Way (TNW) need to be set up first — prior to the further clearing of the forest after Phase 1. This will at least allow the wildlife to disperse to whatever available green refuges outside the Tengah development zone. Otherwise, the problem of wildlife roadkills will be re-enacted as in the tourism development at the Mandai Lake Road recently. Most importantly, some core areas must be designated and left untouched for the future survival of the wildlife within the Tengah Forest itself — so that some, if not all, of the forest-affiliated species recorded there will still have a home for their long-term survival”.

“The Tengah Nature Way is the culmination of the first ever large-scale scheme to promote ecological connectivity, guided with ecological principles, in our town planning processes and we are certainly heartened by this bold plan, but given the rich biodiversity that exists at Tengah Forest, more should be done in terms of biodiversity protection for both resident and migratory species through the setting aside of some parts of the forest as core habitats.”

“Nature Society’s Feedback on HDB’s Tengah Baseline Review” (June 2020)

5. We need to focus on redeveloping alternative sites or brownfield sites such as underutilised lands and abandoned schools etc, in order to achieve a better and more sustainable future for ourselves and our future generations

As mentioned earlier, we should also focus on redeveloping brownfield sites within reasonable distance from existing town amenities and infrastructure, such as vacant lands (such as mowed lawns in Bukit Batok, Jurong, Choa Chu Kang, etc), underutilised lands (such as open carparks), abandoned schools (such as the now defunct Jurong Junior College), etc, as well as building taller apartment blocks (within the vicinity and/or elsewhere in Singapore) where possible in order to make up for any shortfall of planned flat units.

Just as the SG Green Plan 2030 advocates that “Reduce, Reuse and Recycle” will become a norm for citizens and businesses, with a national strategy to address e-waste, packaging waste and food waste, we should apply the same 3R principle for recycling our existing built-up lands in order to conserve Tengah forest (and other secondary forests such as Clementi forest, Dover-Ulu Pandan forest, Bukit Brown forest, Pang Sua woodlands, Kranji forest, Sembawang woods, etc) as much as possible. This will ensure that sustainable development will be a living reality for us all. In fact, the following statement released by the Ministry of National Development also supports the move to recycle existing built-up lands.

“In the past, we could build new homes on swathes of undeveloped open land. Now, after 55 years of building and development, there are far fewer of these, and it has become more challenging to balance competing uses for land. In order to continue providing good homes for Singaporeans, we will have to recycle previously developed land.”

Indranee Rajah, Second Minister for National Development, “Striking a balance in building HDB flats in prime locations” (10 June 2021)

Last but not least, it appears that the upcoming Tengah forest town is designed not so much to accommodate genuine home buyers who may be facing prospects of homelessness, but rather to appeal to property investors. The article “Residential hotspots: Districts shaping up to be interesting investment bets” (1 April 2021) reveals such intent with key words like “investors”, “home upgrading”, “property market”, etc. For example, it states “Home-owners in Tengah are likely to look towards the nearest growth centre, JLD (Jurong Lake District), for home upgrading opportunities after serving out their minimum occupation periods (MOPs). While there are no current launches in the JLD, projects such as Parc Clematis and Clavon have seen positive reception from the market as investors buy into the growth potential of the JLD.”

This trend of home upgrading and property investment shows that public housing today is a far cry from what it used to be in the 1960s when many people had lacked safe housing with proper sanitation. Hence, is it justifiable that we continue to sacrifice our few remaining secondary forests to build more BTO flats instead of redeveloping underutilised lands? We are talking about existential threats to our native flora and fauna because it is a matter of life and death for them, whereas for many of us, it is just a matter of material comfort and convenience rather than basic survival or a real housing crisis.

In other words, the proposed development of Tengah forest town seems to be a case of “induced demand” for public housing. There seems to be a growing trend that many people buy BTO flats not because they have no place to live or have a genuine need to move out of existing homes, but rather because more supply of flats invites people to buy property for upgrading and investment.

In the context of climate emergency and biodiversity loss, even if there are people who have a genuine need for new housing or if they want to upgrade and invest in property, it should be better for them to consider resale flats, private property, etc, or at the very least, choose locations where BTO flats are built on existing built-up lands such as mature housing estates, rather than our precious few remaining greenfield sites, such as secondary forests like Tengah forest, Dover forest, etc.

Summary

In view of the sheer importance of Tengah forest for dealing with climate emergency and biodiversity loss as well as improving our quality of life, it would be very much appreciated if the authorities could:

- preserve the rest of Tengah forest as much as possible, or at least 30 to 50 percent of its original 700-ha size (or 210 to 350 ha) for purifying the air, cleaning the soil, removing pollutants, cooling the urban heat island effect, supporting biodiversity, preventing/mitigating the risk of floods, zoonotic viruses, dengue diseases, saving electricity usage for air-conditioning, enhancing our physical and mental health etc, thereby potentially saving billions of dollars of public funds and personal/household expenses, in terms of healthcare, socioeconomic and environmental costs.

- allocate the aforementioned two core habitat areas within Tengah forest to serve as essential resting/feeding/breeding spaces for wildlife, as proposed by NSS

- designate eco-links in both the western and eastern parts of Tengah forest to facilitate safer and easier movement of wildlife along the ecological corridors and nature areas between Western catchment areas and Central catchment areas

- ensure that the wildlife moving along the long, narrow Tengah Nature Way are protected from traffic noise from the expressway and potential human disturbances from the surrounding new/upcoming residential areas as much as possible

- release the latest EIS report on the north of Tengah to Nature groups and members of the public for our feedback and review when it is ready for early engagement in the planning and development process, before any further development work starts and before any developer is awarded the tender for any construction project done in Tengah forest.

The last point is in line with the key changes made to the existing environmental impact assessment (EIA) framework in 2020, which include the following:

“The third change to the framework will see the planning process – and not just the development work itself – become more sensitive to Singapore’s natural environment. This will be done through earlier engagement with nature groups in the planning and development process, and through the introduction of a course on basic ecology and the EIA process for planners from development agencies.”

“Development works in Singapore to be more sensitive to wildlife under changes to EIA framework” (25 October 2020)

“We have to look at forests as a whole and not in compartments. You cannot talk about intact forests without talking about the wildlife that lives in the forest. So even if you preserve a green corridor or a strip of greenery, but if it’s an inadequate space for wildlife to really thrive in, that’s not fully protecting our biodiversity.”

Dr Andie Ang, a Mandai Nature Research Scientist and President of the Jane Goodall Institute (Singapore), “After Dover, Will Clementi Forest Be Next On The Chopping Board?” (5 June 2021)

Leave a comment