I am a resident of Bukit Batok, and I work as a freelance writer, editor, photographer and videographer. I have worked with the Ministry of Education on Geography textbook projects for secondary schools, and I am also the author of the open petition letter in support of the conservation of Bukit Batok Hillside Park area to ensure a sustainable future for us.

Although I don’t live near Dover-Ulu Pandan Forest (aka Dover Forest), I occasionally cycle around the vicinity, due to my shifts in Clementi zone or Bukit Timah zone as a part-time food delivery cyclist. I can vouch for the fact that the air there often feels cooler and fresher, especially along the Ulu Pandan Park Connector Network (PCN), thanks to the presence of Dover Forest next to it.

In fact, it is found that a single healthy tree can have the cooling power of more than 10 air-conditioning units, and trees can filter air pollution, “improving our health and that of the planet”, according to Ms Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). She also said:

“one of the best technologies for tackling overheating cities was invented long before humans appeared: trees”

“Dover Forest: Don’t sacrifice trees for space” (Straits times forum, 18 February 2021)

Does that mean we can replace Dover Forest with residential buildings, so long as we incorporate some greenery by planting trees around the new Build-To-Order (BTO) flats to cool the air?

No, I don’t think that is advisable in view of the climate change facing us. Instead, I strongly suggest that we should conserve Dover Forest entirely as a nature park-cum-public park (as also proposed by Nature Society), rather than destroy the forest partially or wholly for housing development.

How Dover Forest helps to deal with climate change: Size and density matter

Climate change is an existential threat caused by increased greenhouse gas emissions due to rapid deforestation, urbanisation and industrialisation in Singapore and around the world. Every day, automobiles and factories running on fossil fuels emit tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and there are fewer and fewer trees available to serve as carbon sinks.

In view of the climate change, we need every sizeable forest (of at least 10 ha), such as Dover Forest, in order to mitigate the negative effects of climate change, such as global warming, more frequent extreme weather changes resulting in flash floods or droughts, as well as increased danger to food security and biodiversity.

We must not forget that Singapore is located at 1 degree north of the Equator and experiences a hot, humid and wet climate. Hence, all the negative effects of climate change pose a significant threat to our safety, health and well-being, as well as quality of life, and ultimately our very survival as a human species in the long-term.

On 1 February 2021, the Singapore Parliament rightfully stated:

“That this House acknowledges that climate change is a global emergency and a threat to mankind and calls on the Government, in partnership with the private sector, civil society and the people of Singapore, to deepen and accelerate efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change, and to embrace sustainability in the development of Singapore.”

Parliament declares climate change a global emergency (Straits Times, 1 February 2021)

Although the Singapore Green Plan 2030 has called for 1,000 hectares to be set aside for green spaces and one more million more trees to be planted across our island, it fails to include our responsibility to conserve our remaining dense secondary forests and redevelop brownfield sites instead of sacrificing our forests.

Studies have shown that sizeable forests that are at least 10 ha in area are more effective in cooling the surroundings than fragmented green spaces (such as many of our small parks and gardens).

For example, a research article reveals that:

“The results of the present study illustrate that the highest cooling effect distance and cooling effect intensity are for large urban parks with an area of more than 10 ha; however, in addition to the area, the natural elements and qualities of the urban green spaces, as well as climate characteristics, highly inform the urban green space cooling effect.”

Urban green space cooling effect in cities, Heliyon, Volume 5, Issue 4, April 2019, e01339

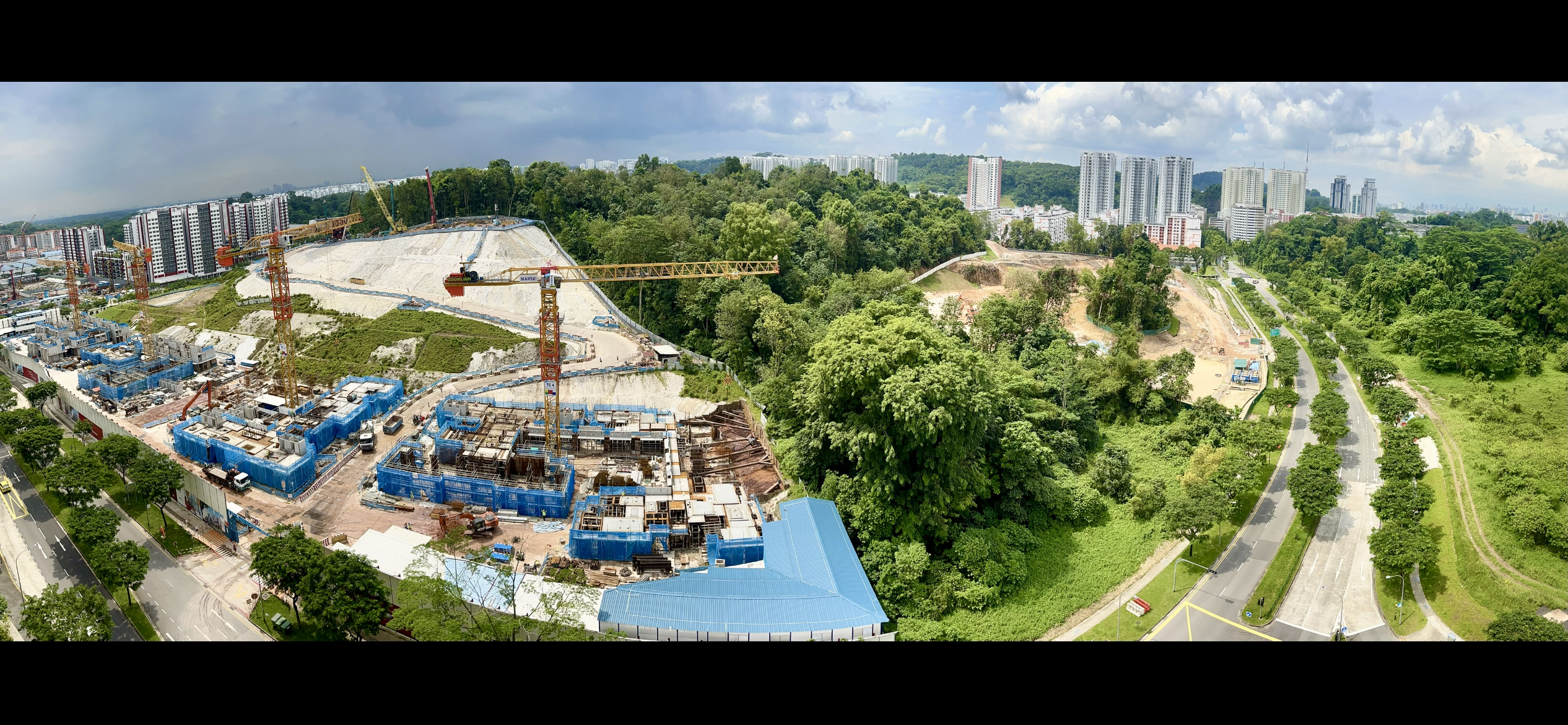

With an area of more than 30 ha of mainly densely growing trees (except for the small patch of grassland in the middle), Dover forest is considered sizeable enough for providing a significant cooling effect on the surroundings, which is more effective than that provided by our smaller parks and gardens, or roadside trees for that matter.

[to be continued as it takes time to put together the latest data]

Leave a comment